History of Goodwin Woods

History of Heart Pine

History of Heart Pine

Where antique heart pine comes from

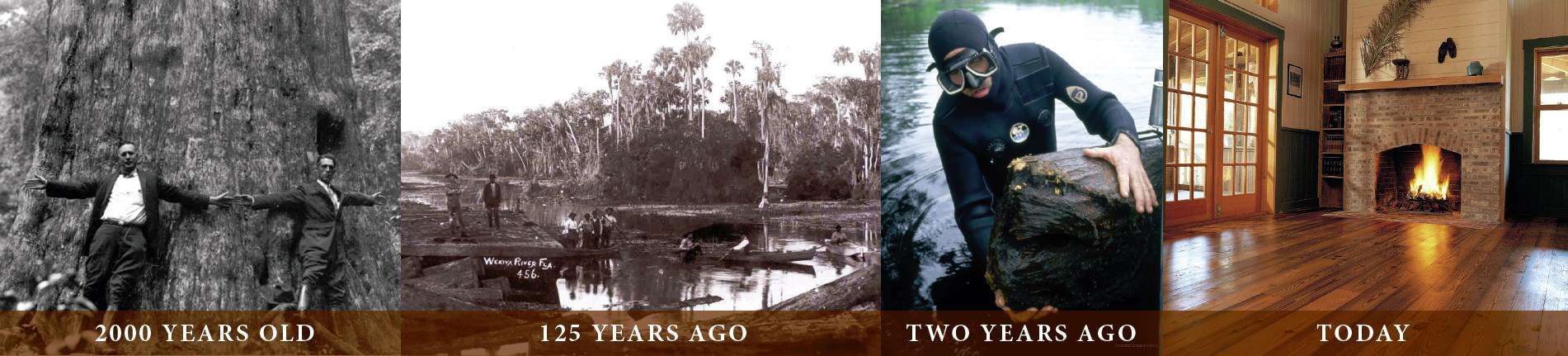

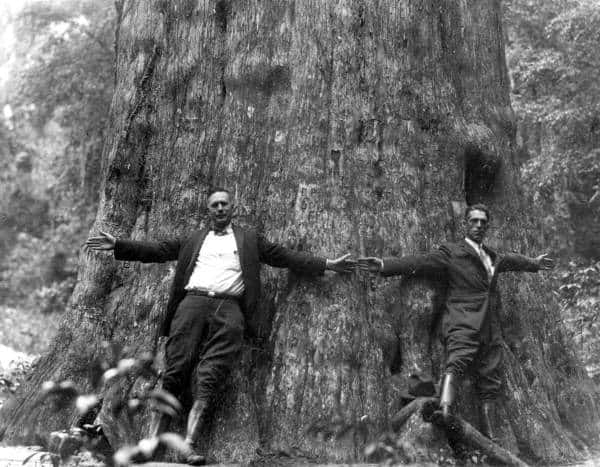

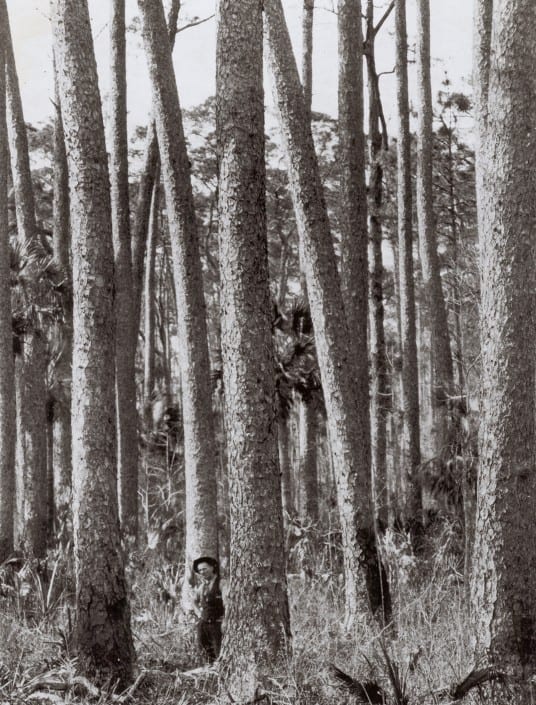

Before the American Revolution, longleaf pine…the source of heart pine…dominated the landscape in the South. Once the largest continuous forest on the North American continent, the longleaf ecosystem ran along the coastal plain from Virginia’s southern tip to eastern Texas.

Where there was once approximately 60 million acres, less than 10,000 acres of oldgrowth heart pine remain today. Put another way, what was once 41 percent of the entire landmass of the Deep South now covers less than 2 percent of its original range. The hardwood trees had been growing for centuries, producing only an inch of growth in diameter every thirty years. It takes up to 500 years for heart pine to mature.

Why heart pine is the ‘wood that built America’

As the United States was formed and began to grow and prosper, settlers quickly discovered the immense value of the towering but slender hardwood trees. Because of its strength and durability, heart pine was declared the “King’s wood” for shipbuilding when America was first colonized. As settlers moved southward, originalgrowth heart pine was steadily logged and was used for log cabins in the 1700s and 1800s, and later for the construction of fine Victorian homes, hotels and palaces. Heart pine once framed four of every five houses in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, floored Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and Washington’s Mount Vernon, and buttressed the keel of the USS Constitution (“Old Ironsides”).

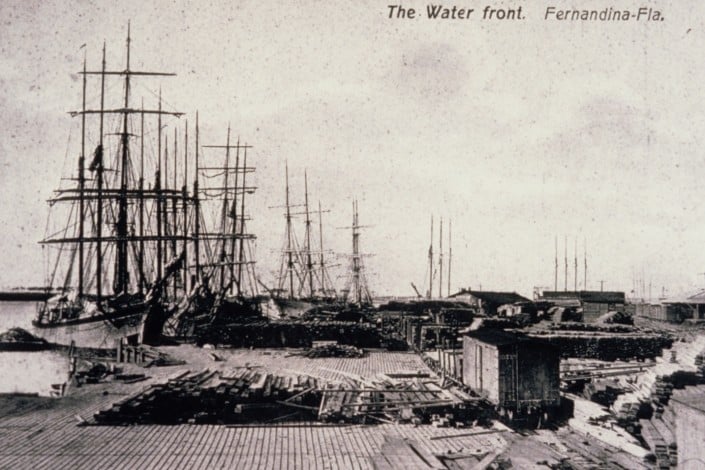

Heart pine played a key role in the growth and development of the United States as an economic power. As industrial America began to flex its muscles later in the 19th century, heart pine was transported in tall ships made of heart pine up the Eastern seaboard and over to Europe. The Herculean wood provided flooring, joists and paneling for homes and factories, as well as timbers for bridges, warehouses, railroad cars and wharves. Also appreciated for its beauty, it was utilized in Victorian hotels and palaces. Anytime you visit an old building, look around. You are likely to recognize heart pine still hard at work and in excellent condition.

One example is the pilings from the shipping port in Savannah built by General Oglethorpe in the early 1700s. When the dock was torn down a few years ago, Goodwin reclaimed them to provide an antique heart pine darker than most. Once it was milled again, the wood is the color of the heart pine floor in George Washington’s Mount Vernon…without waiting 250 years for the color to age.

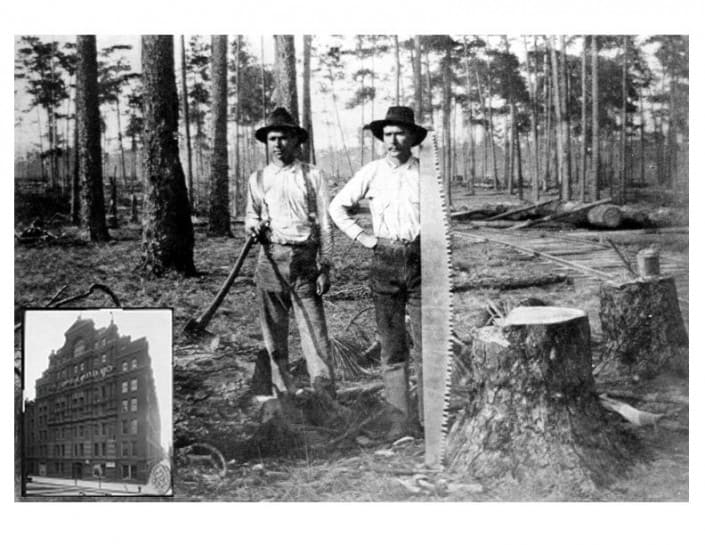

By 1850 the South had constructed only 2000 miles of railroad, so the best way to transport longleaf logs to downstream sawmills was to use the rivers. The common method for timbering was to cut trees with axes and drag logs with oxen or mule teams to the riverbanks. As more and more people moved to the South, lumber companies began to take their crews further inland in search of more heart pine. Loggers dug manmade canals to carry the inland logs to the river.

You couldn’t go anywhere in the South without running into the naval stores industry, which tapped the longleaf for its valuable resin. Longleaf resin was used in paints, soaps, weatherproofing products, shoe polish and medicines and made the U.S. the world leader in naval stores until the middle of the twentieth century. Even baseball players used resin on their equipment and ballerinas on their toe shoes to improve their performance.

Remaining forests protected today

Today, original-growth heart pine is as rare as sunken treasure, with less than 10,000 protected acres of original-growth Longleaf Pine forests remaining. Antique heart pine and heart cypress timbers are revered for their rich history as much as their beauty and durability. Sadly, clear-cutting of the vast southern forests in the late 1800s wiped out virtually the entire range of original-growth heart pine and heart cypress trees. The only place to find the last vestiges of this antique wood is reclamation from old buildings or where it was left behind–under water in the southern rivers used by many timber operations in the 1800s to raft their logs to nearby sawmills.

Goodwin Heart Pine- River Recovered®

Although some of these 1800’s treasures found their way to the river bottom by storms, the densest logs fell off the river rafts used to transport them – lost, it would seem, forever, into the dark tannic waterways.

Preserved in time by the cool waters, these antique logs are treasures, waiting to be found by experienced divers who know what to look for. An ax cut end indicates the tree was likely cut sometime prior to the mid-1880s, before the steam engine came into use in the South. Flat cut ends show that the tree was logged by two-man crosscut saws, used after the mid 1880s. This allowed them to cut trees much faster for rail transport.

Another telltale mark is the presence of “cat whiskers”. These are the marks left by the turpentiners and indicate the tree is a long leaf pine tree, once tapped for naval stores.

History of Heart Cypress

History of Heart Cypress

Heart cypress, from the Bald Cypress tree, is truly a primitive American wood. Bald Cypress trees can grow more than a thousand years old and tower to heights of more than a 100 feet. Once commonly found in virgin stands along rivers and tidewater swamplands of the southeastern coastal plain, the finest cypress grew where the land was submerged most of the year. Cypress logs estimated by scientists to be at least 100,000 years old were unearthed in excavations for the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C.

Heart cypress was logged right along with the longleaf heart pine in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though the forests were not clear-cut like the heart pine. Loggers cut around the circumference of the tree a year in advance of logging to allow the wood to lose part of its moisture so the logs would float. Because there was only about 2000 miles of railroad in the South by1850, loggers would hand cut the heart cypress trees and drag them by oxen or mule teams to the riverbanks. There they would lash the logs together and float the raft to downstream sawmills.

Today the silvery trunks and fernlike leaves of the Bald Cypress still grace southern riverbanks. Some are 100 years old or more left from the previous century’s logging.

Others still stand, dead but showing where they were marked and cut, but never brought down. Unfortunately, the wood from young cypress trees does not compare to the rich-toned heartwood of original-growth heart cypress.

Through centuries of adaptation, Bald Cypress has developed an inherent resistance to destructive forces, including water and insects, not found in other woods. A favorite building material of Frank Lloyd Wright, heart cypress is a natural building material for flooring, furniture, exterior walls and many other special projects.

Characteristics of Heart Cypress

Honey tones: rich red tans to light chocolates

Beauty: uniquely fine grain often provides a feathery pattern

Durability: can be used as interior or exterior wood

Rarity: 100% heart cypress is more rare today than heart pine

Longleaf Ecosystem

Longleaf Ecosystem

Towering Value

A tree that lives 50 years provides services worth $196,250 in its life.

(a 1990 Earth Day brochure estimated)

- Protein Production $2,500

- Recycling water humidity control $37,500

- Air pollution control $62,500

- Soil fertilizer and erosion control $31,250

- Wildlife shelter $31,250

- Oxygen production $31,250

Sources: U.S. Forest Service, Timber Association of California, U.S. Bureau of Land Management and California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Longleaf Pine Forest Overview

Longleaf pine is also known as long needle, long straw, southern yellow, hard, pitch and Georgia pine among other names. The natural range of longleaf pine extends from southeastern Virginia to east Texas in a belt approximately 150 miles wide adjacent to the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. It dips as far south as central Florida and widens northward into west central Georgia and east central Alabama. It occupies portions of three physiographic provinces: the Southern Coastal Plain, the Piedmont, and the Appalachian foothills.

Longleaf pine-dominated forests can prosper on a variety of soil types, moisture regimes, geological formations, and topographic features across the wide geographic range of the species – in short, they grow almost anywhere. The tree’s species name (Pinus palustris) means “of the marsh.” Yet longleaf today is found mostly on dry upland areas, as the moist fertile sites were the first to be cleared for farming.

Longleaf-The Virgin Forest

“The virgin forest offers excellent opportunities for studying the life-histories of trees. …. Several investigations of the life history of the longleaf pine, including observations under virgin forest conditions, have been made within recent years. There is, however, a practical value in pursuing still further the study of this tree. The longleaf pine is commercially of the very first importance. It is extensively distributed throughout one of the best timber-producing sections of the United States and is very well adapted to systematic forest management. Within recent years new and improved methods of exploitation have been managed with too little regard for the future and the supplies are quickly melting away. Only when the treatment of these forests shall be brought into accordance with the natural requirements and life-tendencies of the tree will the best results of the present as well as the future be assured.”

Excerpt taken from: The Longleaf Pine in Virgin Forests, Schwartz GF, 1907.

Why Did Longleaf Once Dominate?

Before the Europeans arrived in the New World, longleaf pine was the principal tree species found in extensive pure stands over at least 70 million acres and another 10 million acres in stands mixed with other pines and hardwoods.

The reason longleaf dominated is that it, more than any other southern tree, has learned to live with fire. The original longleaf forest not only was able to survive the frequent fires started by lightning, it depended upon fire. It may actually have helped propel and sustain the fires that regularly burned it.

The longleaf has evolved marvelous physical adaptations to tolerate fire when young. Instead of growing upward right away as most saplings do, longleaf seedlings “sit” flat on the ground in what is termed the grass stage for periods of three to fifteen years. During this time the young tree grows a long, heavy taproot that helps it reach far down into the sandy soil toward moisture. When the young plant finally starts to grow tall, the stored food in the taproot helps it shoot rapidly upward.

At the same time that it is racing skyward, the tree delays putting out branches, giving young saplings a distinctive bottlebrush appearance. The tree’s “jumping upward” is a strategy for surviving in an area of frequent fires. By growing rapidly upward in a single spurt, the young tree minimizes the amount of time its growing tip is vulnerable to destruction by fires. Otherwise, a young tree growing steadily year by year and putting out multiple branches would be vulnerable to ground fires for a far greater period.

This variety of adaptations that help longleaf pines resist death by fire, is eclipsed only by a fantastic secondary function of the needles. This supremely fire-resistant tree produces needles that have more volatile resins and oils than any other southern pine, rendering the dry needles extremely flammable.

The Plight of the Longleaf Forest

The seemingly endless longleaf pine forests shaped the recent culture of the Southeast. Rich in a gummy resin that produces tar, pitch, turpentine, and rosin – or naval stores, these longleaf pine naval stores were sought worldwide for a multitude of uses.

Early economics of the Southeast centered on the export of longleaf pine products. Heavy exploitation of the virgin longleaf pine timber began on the Atlantic seaboard after the Revolutionary War and moved inland, then southward, intensifying with the development of railroads in the late 1800’s.

The heyday of the longleaf pine timber industry was reached within the first decade of the 20th Century. By 1930 virtually all of the virgin longleaf pine forest had been cut. Less than 1,000 acres of virgin timber remains today.

Today the longleaf pine ecosystem covers less than 3.8 million acres (over a 94% loss). Virtually all of the acreage is second growth, degraded by logging, turpentining, grazing, and disruption of the natural fire regime. Longleaf forests have been partly or wholly replaced on many of original longleaf sites by other pines and hardwoods due to suppression of fire and establishment of loblolly and slash pine plantations.

Naval Stores and Other Longleaf Industries

From “Longleaf Pine-Dependent Industries,” by Richard Porcher, The Citadel, Charleston, S.C., 1985.

“Naval stores, tar and pitch supplies used by the Navy, were dwindling in the Northern European countries when the New World was discovered. But the production of naval stores and turpentine in this country did not actually begin in the South. The North Atlantic colonies began the process in the 1600s, where pitch pine was used. But as colonists began to arrive in North Carolina about 1665, they soon discovered that the abundant longleaf pine was a more prolific source of tar and turpentine. By 1700 the production of naval stores was an important part of the economy of North Carolina and quickly spread to South Carolina. In 1850 the Carolinas accounted for 95 percent of the total American production.

“Crude turpentine is found in the resin canals of the inner bark and sapwood of various coniferous trees. This gummy fluid is not the sap of the tree. Upon distillation, crude turpentine yields two components; essential oil (spirits of turpentine) and rosin. These products still have many uses today. Spirits of turpentine is important in the paint and varnish industry as a thinner. It is also used as a solvent for rubber, in medicine and in the manufacture of many chemicals. Rosin, a brittle faintly aromatic solid, is used in the manufacture of soap, varnish, paint, linoleum, sealing wax, drugs and oilcloth. It is the chief sizing material for paper.

“But it was tar, not turpentine, that was most important in the early development of the South. In the naval stores industry, tar is the crude liquid that drips from the burned wood during slow combustion. Pitch is a partially carbonized and condensed product obtained by boiling or burning tar. Tar and pitch were among the earliest exports of the country, and the industry was practically the only means of livelihood in the early days of the Carolinas. Indeed, the history of the naval stores industry is closely identified with the economic development of the South. Pitch was used chiefly for caulking wooden sailing vessels and tar to coat the riggings. Eventually pitch was replaced by welding bead and the tarry rigging of sailing ships fell before the steam engine and diesel oil.

“By the turn of the century, the vast longleaf forests of North and South Carolina soon played out, and turpentiners, a migratory lot, began to take their equipment and their help to Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida. By the 1920s, the last of the virgin longleaf forests had been cut throughout the Southeast. Second-growth timber was not as rich in gum as virgin timber, and chemical alternatives to naval stores began to be developed instead. The name “naval stores” continues to be used even though spirits of turpentine and rosin became the major products. Today, many other countries, including China and many South American countries, produce more turpentine and resin than the United States.”

Some Important Dates in Longleaf History

1528, Earliest European application of North American naval stores occurred in present-day Florida near the confluence of the St. Marks and Wakulla Rivers. After failing to rendezvous with the Spanish resupply fleet, Panfilo de Narvaez, exhausted and nearly starved, ordered the construction of five wooden boats. After caulking the hull seams with beaten palmetto fibers, the conquistadors smeared tar made from pine resin on the hulls of these crude barge-like craft to make them watertight.

1584, The continent’s seemingly inexhaustible naval stores resources attracted special mention when explorers visited the Atlantic coastal region in the vicinity of present-day North Carolina and reported to Sir Walter Raleigh that there were “trees which could supply the English navy with enough tar and pitch to make our Queen the ruler of the seas.

1539, Hernando De Soto came ashore from his base in Cuba to Florida and traveled through the piney woods with his band of armor-clad soldiers.

1608, First documented cargo of North American naval stores left Virginia for English boatyards under the leadership of Capt. James Smith.

1714, Introduction of water-powered sawmills. Beginning of removal of saw timber of lands along waterways.

1757, Independent naval stores production in Florida expanded the trade of pitch and tar to Havana, Cuba.

1790, William Bartram explored the longleaf pine forests in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida.

1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin that made growing short-staple cotton profitable. Many virgin stands of longleaf pine were felled to provide farmland.

1815, First steamboat in the Carolinas; 10 in use in South Carolina by 1826. Introduction of steam power marks the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the South.

1816, During the so-called “year without a summer” the ground remained frozen in the northern United States so that crops could not be planted. The rings produced by many trees during this year are strongly distorted and some trees produced no growth rings at all.

1834, Introduction of the copper still for distillation of turpentine. Beginning of era of massive turpentining operations.

1860, Feral hogs reach saturation density on open range in much of the southern range of longleaf pine.

1880-1890, Beginning of standardized railroad track sizes. Concatenation of isolated railroad lines, making overland transport of lumber feasible.

1891, Congress authorized withdrawal of lands from the public domain for a system of forest reserves to secure a future supply of wood products for a growing nation.

1907, G. Frederick Schwarz’s book, The Longleaf Pine in Virgin Forests, documents the remaining virgin longleaf pine in the Gulf states, from western Florida to western Louisiana.

1914, Death of the last passenger pigeon, Martha, in the Cincinnati Zoo.

1933, Herbert Stoddard published The Bob White Quail: Its Habits, Preservation and Increase, showing how bobwhite quail could be increased in longleaf pine forests by using fire management.

1943, Forest Service gives general approval for use of fire in managing woodlands.

1946, Publication of The Longleaf Pine by W. G. Wahlenberg, the best-known study of longleaf pine.

1979, Conservation easement granted for the Wade Tract, the most studied old- growth longleaf stand in existence.

1994, The first region-wide conference is held by the U.S. Forest Service to coordinate an agenda for longleaf ecosystem restoration.

The History of a Tree

From “Tree 249-3,” by Larry Hedrick (U.S. Forest Service, Hot Springs, Arkansas), Alabama’s Treasured Forests, Spring 1992.

“The story of 249-3 is not entirely unique, for there are many such longleaf trees in the Talladega National Forest. The original forest of which they are a part is gone and, with it, the possibility to completely know the ecological workings of virgin old-growth longleaf forest. Still, one wonders what knowledge about the ecological functioning of that forest can yet be gleaned from the study of these relict members. …A simple reverence for antiquity, a sense of history, and an appreciation of tenacity dictate that these old trees and the modern-day longleaf forest of which they are a part be accorded a special place in the treasured forests of Alabama.

“Today, in its 360th year, with a diameter approaching 14 inches and still supporting an active red-cockaded woodpecker cavity, tree 249-3 stands in the Talladega National Forest.

“In April of 1639, fully seven years after germination, our seedling finally began to grow skyward. Rapidly at first, then ever more slowly it grew, having to content itself with what sunlight filtered through the canopy far above. It persisted.

“For the period 1700-1799, the tree garnered the canopy-filtered sunlight of 100 springs and summers. This is recorded in 200 extremely narrow and alternating rings, light wood of spring and dark wood of summer. The accumulated capital from these 100 years of subsistence was but 2 inches of diameter growth. The tree was 167 years old and 6 inches DBH (diameter at breast height).

“At the end of the nineteenth century, our tree had persisted for yet another 100 years and accumulated another 1.9 inches in diameter growth. The forest in which it grew was largely intact. At 268 years of age, the tree measured some 7.9 inches DBH. Remarkably though, owing perhaps in part to its subordinate canopy position, and in part to its advanced age, fully 80 percent of this girth was comprised of heartwood.

“In 1917 the longleaf stand containing our tree was logged. All accessible trees meeting merchantability standards were taken. Owing to its small size (8.4 inches in DBH) and its subordinate position in a forest of large high quality trees, our suppressed tree and others like it were not taken.

“For our tree, this release from the shading effects of the overtopping forest dominants was of singular importance, and at the age of 285 years it responded with an increased growth rate. This patient ability of longleaf pine to respond to releases at advanced ages receives no mention in modern forestry texts. Rejoicing in its now unfettered place in the sun, with its crown expanding rapidly, it grew at a rate far surpassing that of its previous years.

“In 1937, at 305 years of age and having acquired more growth in the last 20 years than it had accumulated in the previous 100, the tree was 11.6 inches in diameter. The 1950s and early 1960s would see continued forest growth, both of young trees and old. And for the first time since the cutting of the virgin forest many years before, this new forest began to produce wood products as the dense young stands were thinned to increase growth of residual trees.

“Sometime in the early 1970s, a member of a red-cockaded woodpecker clan excavated a roost cavity in our tree. Remaining clan members excavated cavities in other nearby relict longleafs.

“For 360 years it has avoided the pitfalls of catastrophic natural events like crown fires, lightning strikes, tornadoes, and insect depredation, and some unnatural ones like the foraging of free-ranging hogs, to become a part of our modern landscape.”

What is a Growth Ring?

The inner part of the annual ring is produced in spring, when growth is rapid, and is made up of thin-walled cells with large pores. The outer portion is produced more slowly in summer and its cells have thicker walls and the pores are smaller. Together the pair comprise what is commonly called a growth ring.

Some of the dark summer rings are interrupted by spurts of late growth probably caused by heavy summer rains. Thus, tree rings contain weather records. Tree rings also tell us when there is a lot of rain. About every 100 years about 15 rings occur that are four or five times the width of the others. This indicates that during those years the rainfall was heavy.

In his 1964 book This is a Tree, Ross Hutchins says, “In addition to their other uses to mankind trees also help us unravel the secrets of the past and perhaps even to peek into the future. A tree’s memories are recorded in its rings.” (See the story above that comes from the growth rings of tree 249-3)

How Do I Know if It’s a Longleaf?

One of the major differences in Longleaf’s appearance from other pines are the long needles that form spheres at the end of stout twigs. It has the largest cones of any of the Southern pines.

The young longleaf pine makes one of the most striking features of southern forests. When five to 10 years of age, the single upright stem with its long, dark, shiny needles forms a handsome plume of sparkling green; while in later youth the stalwart, sparingly branched sapling, with its heavy twigs and gray bark, attracts immediate attention. The old trees have tall, straight trunks, most one to two feet in diameter, and open, irregular crowns, one-third to one-half the length of the tree.

Longleaf stands, found throughout the southern coastal plain, today reflect a history of extensive naval stores operations, logging, and burning following the logging. As a result many longleaf pine forests have been replaced by other species.

The leaves or needles are from 10 to 15 inches long, in clusters of three, and gathered towards the ends of the thick, scaly twigs. The flowers, appearing in early spring before the new needles, are a deep rose-purple turning to silver-white. The ample flowers grow in prominent, short, dense clusters, and the female flowers occur in inconspicuous groups of two to four.

The cones, or burrs, are six to 10 inches long, slightly curved, with thick scales armed with small curved prickles. The cones usually fall soon after the seeds ripen, leaving their bases attached to the twigs.

The distinctive large cones develop from female flowers over a two-year period. Seeds are dispersed by wind beginning in late October and continuing through November with most falling within a two to three week period depending on weather conditions.

Many animals, including wild hogs, fox and grey squirrels, and many types of birds feed on the large, tasty seeds. Longleaf seeds are the largest of the southern pines and differ from the others in that the seeds germinate soon after they reach the ground. If conditions are right they can germinate in less than a week.

Excerpts taken from: Forest Trees of Mississippi, Mattoon and Beal, 1929

The Longleaf Growth Cycle

From October to December the large, succulent seeds are shed from the big cones that have taken two years to form. Both male and female flowers occur on the same tree, but it is hard to see the female flowers until the beginning of the second year. The male flowers produce the bountiful yellow wind born pollen early every spring, usually March. Carried to the ground by their propeller or papery wing, the seeds normally fall within feet of the parent tree and germinate almost immediately. By the following summer, when most fires occur naturally, they will be well-rooted seedlings with a cluster of true needles.

A longleaf pine does not usually bear cones until it is 20 to 30 years old. Although some cones form every year, a major bountiful cone and seed crop occurs only every five to seven years. Sometimes one region will have a good cone crop while another won’t. Other times trees throughout the entire range will be prolific. For example, 1993 was a good year for cone production throughout the Gulf Coast region.

Though nothing seems to be going on, the hidden roots are actively growing downward, forming a long, thick taproot. This sturdy taproot will securely anchor the tree as it grows skyward. The taproot can grow to a depth of eight to10 feet while the trunk attains a height of 100 feet or more. The taproot can supply water from great depths during periods of drought, while the numerous horizontal roots within two feet of the surface rapidly take up moisture. Although it is not obvious, seedling growth can be determined by the increase in root collar diameter just at the ground; when the diameter is about one inch, rapid upward growth is about to begin.

The stored food in the taproot supplies the energy the young plant needs to bolt out of the fire-resistant grass stage. As it grows, few branches form and the young tree looks like a bottle brush. Its rapid growth and lack of branches reduce the vulnerable period when fire can harm the growing tip. While between two and three feet in height, the seedlings are most susceptible to damage by fire, climate and mechanical damage. After this upward growth spurt begins, the young tree will reach a height of at least five feet in one year.

A dense stand of young trees will develop and gradually thin out as the trees compete for light, water, and nutrients. A few trees will outgrow others and overtop the young stand that has developed in an opening in the forest caused by lightning and fire, hurricanes or timber harvest.

Longleaf pine is a long-lived species and can grow to the ripe old age of 300 to 400, more like a hardwood in its growth pattern than other southern pines that begin to decline with age when they reach the century mark. Longleaf grows somewhat more slowly than other pines, particularly as seedlings and saplings, but it continues to put on girth throughout its life and can actually accelerate its growth rate in old age when competing trees die or are harvested.

Excerpts taken from: How Does Longleaf Grow? by Julie Moore

Critters of the Longleaf Forest

Tree dwellers and burrow users, large species and small, predators and prey – all thrive in the two-layered longleaf pine forest. Although the pines themselves provide seed and bark-dwelling insects, it is the groundcover that supplies a diverse menu of succulent grass foliage, seeds of herbs and grasses, fruits of low-growing shrubs and tender underground roots. The greater the amount of moisture and the richer the soil, the more plants a particular longleaf association can support.

Mourning and ground doves, meadowlarks, various blackbirds as well as fox squirrels, rodents and ants consume the large longleaf seeds that sail downward from the cones beginning in October. Red-headed and red-cockaded woodpeckers, sapsuckers, and nuthatches glean insects from the tall, straight tree trunks and high branches. Living and dead trees provide nesting cavities for woodpeckers, blue birds, kestrels, flying squirrels and even wood ducks.

Gopher tortoises, white-tailed deer and rabbits feed on tender shoots of bunch grasses (wiregrass, dropseed, little bluestem) that sprout following a fire. Early travelers even recorded bison and elk grazing in heavily grassed sites within sectors of the original longleaf forests. The dense clumps of wiregrass and other bunch grasses provide cover, nesting sites, and seed for the bobwhite quail.

Gopher tortoises feed mainly on low-growing plants, particularly wiregrass, broadleaf grasses and legumes. They also eat pawpaws, blackberries, palmetto berries and gopher apples. With their shovel-like front legs, gophers excavate a burrow up to 30 feet long and 10 feet deep that maintains a fairly constant temperature and high humidity. More than 300 animals have been known to shelter in these burrows, including indigo snakes, gopher frogs, Florida mice, skunks, opossums, rabbits, bobwhite quail, burrowing owls, and unknown numbers of invertebrates. The burrows provide escape from predators, fires and adverse weather for creatures that cannot create their own. The Gopher Tortoise: A Species in Decline, the Gopher Tortoise Council.

Overnight, the mysterious, seldom-seen pocket gopher (also called a “sandy mounder” or dry land salamander) leaves its distinctive mounds of bare soil as it burrows rapidly beneath longleaf pine forests. This vegetarian is searching for tasty underground plant parts and is fond of the bark and stems of young longleaf seedlings. So were the pineywood rooters (feral hogs) set free by early settlers.

Rodents, birds, frogs, snakes, and lizards are food for great horned owls, loggerhead shrikes, and bobcats today as they were for panthers and wolves in the distant past. Omnivorous feeders like gray foxes and black bears move in and out of longleaf woodlands as berries and other fruits ripen and insect levels peak. Today, quail and other ground-feeding birds also make good use of seasonally high insect populations.

All of these species and many more use the longleaf forests for part or all of their life cycles. They evolved within the fire-maintained landscape and have adopted behavior patterns and mechanisms, such as sheltering in burrows and nesting in tree cavities, to escape the periodic, low-intensity ground fires that moved across the landscape.

The Diversity in Longleaf Groundcover

Visually the longleaf forest is deceptive. At first glance it looks to be mostly unbranched pine trunks, now and then an oak or hickory and lots of knee-high grass. But this is a subtle landscape where minor changes in elevation, slope and soil make for major changes at ground level. You have to get out of your vehicle and put your feet on the ground to see the incredible variety of herbaceous and woody plants that grow here.

If you begin your tour on a dry sand ridge with coarse, nutrient-poor sands and limited moisture, the numbers of plants and species will be unimpressive, though the individual types can be quite intriguing and beautiful. On desert-like edges grow plants adapted to baking sunlight and little water, like the spurge ipecac, sandwort, wire weed, blue lupine and the diminutive pixie moss that flowers in winter.

As you move down slope, the soil grows wetter and soil is more finely-textured. More plant species will be found here. There will be more legumes, nitrogen-fixing members of the bean family that produce some of the best natural wildlife foods. Sunflower relatives like golden aster, liatris, rayless goldenrod, narrow-leaf sunflower and black-eyed Susan appear. Grasses like little bluestem, dropseed, and lopside Indian grass join the groundcover. And the low-growing shrubs — dwarf wax myrtle, blueberries and huckleberries, New Jersey tea, ink berry and dwarf chinquapin — make appearances. If the site has been burned regularly, there will be even more occurrences of these plants.

Moving downslope to level land, where water may actually stand for brief periods, the true floral splendor of the longleaf forest can be witnessed. Packed together are the curious insectivorous plants – sundews, pitcher plants, butterworts and (in coastal North and South Carolina) the Venus fly trap. Orchids are plentiful, some single- lowered, others with tiny perfect orchids covering a tall stalk. Purple-flowered vanilla roots, red Catesby lilies, orange and yellow milkworts, and hot pink meadow beauties sway in the breezes.

The Role of Wiregrass in the Longleaf Ecosystem

“Wiregrass is a “keystone” species of central importance to the longleaf pine community. This grass added to longleaf pine straw comprises the primary fuel base for frequent fires. At least 150 rare plant species, literally hundreds of other plants, and many wildlife species are closely associated with wiregrass.

“When burned, this extremely flammable grass reduces woody brush much better than any other type of ground cover vegetation. Management of lands without wiregrass must include much more use of machinery (mowing, disking) and manpower to control brush.

“Wiregrass is ideal for nesting cover of quail and many other ground-nesting birds and concealment cover from predators. Wiregrass encourages quail coveys to “freeze-hide” rather than run when bird dogs approach, thus improving hunting success, and wiregrass seed are eaten by turkey, particularly the young of the year.”

Excerpts taken from: The Benefits of Wiregrass, by Larry Landers

The Role of Fire in the Longleaf Landscape

In the past 200 years, settlement of the Coastal Plain has drastically altered the normal summertime fire cycle. Not only were fires actively suppressed when they started, but roads, towns, agricultural fields, and other constructs of man have impeded the widespread, weeks-long slow-burning fires that swept the Coastal Plain regularly in pre-settlement times.

Without summer fires to trigger flowering, many ground cover species are unable to set seed and reproduce. And without periodic summer fires abundant reproduction of the longleaf pines themselves is limited. Suppression of fire has resulted in a gradual drift from majestic, open longleaf pine forest with dense wiregrass and numerous herbs to a dense hardwood forest and scrub oak thickets with negligible ground cover and little wildlife. And with it vanishes the ideal habitat for man, animal and plant species, as well as longleaf “specialists,” the fox squirrel, Red- cockaded Woodpecker, and the diminutive pixie moss.

Controlled Burning

The following information is taken from

Seasonal Effects of Prescribed Burning in Florida, by Robbins and Myers, 1992.

“The number of lightning fires peaks about a month earlier than the peak number of

thunderstorm days. Similarly, acreage burned by lightning fires does not strictly parallel the distribution of numbers of fires — the area per fire is greater in the summer. What is responsible for these discrepancies? The most obvious explanation is rainfall. Fuel moisture is one factor determining whether a lightning strike ignites a fire and how large a fire gets. Lightning strikes in Florida may tend to ignite and burn large areas early in the growing season because surface fuels have not yet become moisture laden by daily rainstorms.”

What’s Bad About Fire

Not all native forests are tolerant of fire. Deep bottomland hardwoods that once grew along major rivers probably did not burn except during periods of extreme, prolonged drought. Longleaf, even though fire tolerant, can be killed by fire if burned when there is a thick mat of needles, cones and branches accumulated from years of fire exclusion. The fine horizontal roots move up into the slowly decomposing organic litter. Then even a smoldering fire that slowly burns off the accumulated fuel will effectively girdle the tree by killing these surface roots unless the accumulation is removed before burning.

Wildfires also can be extremely destructive when accidentally started in areas where natural and prescribed fires have been excluded for decades. In forests that would naturally burn, the probability of wildfires is increased if fuel is allowed to accumulate and burning is excluded. The best thing for longleaf, and some other pine forests, is a regular burning program to keep the woods floor clean and green and to promote natural forest regeneration.

Without Fire What Happens?

Because of their large root systems and elaborate runners, scrub oaks, water and willow oaks and other hardwoods like sweet gum and hickory are constantly ready to grow, and the absence of fire provides them the opportunity they need. Stems sprout, new stems grow, leaves proliferate, and trees shoot up toward the bright sunlight between the widely spaced pines.

Normally, fires kill this growth back every few years. When there are no fires, the oaks keep on growing until they form a scrub oak thicket. The ground under dense oaks is shaded from light and covered with leaf litter. Longleaf seeds and seedlings don’t have a chance there. Without fire to prune back the oaks and other hardwoods, the towering longleaf is consumed by a mass of hardwoods. The big pines die of age, with no little ones to replace them.

Longleaf sounds too good to be true. What’s the catch?

“Essentially there is no catch. The only difficulty can be the establishment of a longleaf stand as it is not as easy to artificially regenerate. If you plant a longleaf seedling too deep or too shallow it will not survive. You have to intensively prepare a seed bed to plant at the right depth that increases your site preparation expense. Once planted and managed, however, a longleaf stand is easy to regenerate naturally, virtually eliminating future reforestation expenses.

“A vast majority of landowners require income to be able to pay for and maintain their land. Other pine species can be artificially regenerated without the extensive site preparation that lessens the expense of establishment. Those species, primarily slash and loblolly, are generally clear-cut every 30 years and then replanted. This results in reforestation expenses, averaging between $150 to $180 per acre, every 30 years. If you can establish a longleaf stand you eliminate this expense.

“The major problem I foresee is resistance to control burning. Current trends make it difficult to burn, and that makes it difficult to manage longleaf. Fire is mother nature’s primary tool in slowing forest succession from a pine to a hardwood forest. Almost all states require permits before you can burn and do not allow burning near roads, homes or other areas in which people will be affected by smoke from the fire. Florida requires that all controlled fires be extinguished by a certain time that restricts the amount of area that can be burned and increases the expense of burning. If we cannot burn we cannot manage for longleaf.”

A New Popular Product – Pine Straw

Baled longleaf pine straw has become a popular landscaping product. It is slow to decompose, contains few weed seeds, helps retain soil moisture and has an attractive red hue. It is a good mulch for use by nurseries, farmers and landscapers.

A young pine plantation on a fertile site can begin producing straw for harvest within 8 years. Annual or biennial raking of high quality “red straw” from weed and shrub free plantations is an additional incentive to plant longleaf on retired agricultural fields. Homeowners currently pay $2.50 to $4.00 per bale. Harvesting can increase the total return per acre and provide more regular income.

Please note that over zealous removal of straw, particularly in natural stands and those managed for wildlife, can eliminate the same benefits it provides in the yard and garden. Intensive straw harvest can damage ground cover plants that provide food and cover for animals and removes fuels essential for keeping fire in the longleaf forest. Pine needles serve vital functions in the forest ecosystem.

An Interview with Three Longleaf Foresters

The foresters are Bill Boyer, of the Escambia Research Station in Alabama and Auburn University; Leon Neel, who practices “ecological forestry” and manages a protected longleaf stand in Thomasville, Georgia; and Bob Farrar, a forest research consultant.

What are your long-term predictions about the fate of native longleaf forests?

Boyer – “The future rests with the private owner. Recent information will prove that it is economically feasible to grow longleaf. The private sector is where it is at. We must work with the private owner to reduce the rate of loss. Since the last Forest Inventory Survey in 1989 over 1/2 million acres of longleaf have been lost. Good prices recently for saw timber have caused this. The disincentives to the landowner to grow longleaf need to be eliminated. I believe land in longleaf forests will stabilize during the next 25 years between 2.5 and 3.5 million acres.”

Farrar – “Longleaf will survive on National Forest, National Park Service, military lands and Nature Conservancy preserves. But I am not convinced that on various state lands longleaf will survive.”

Neel – “Fire liability issues just about guarantee the demise of longleaf on private lands. The liability coverage is becoming too expensive for private landholders to have their lands burned. Public lands are the hope for longleaf. Continuity of management practices over more than a human lifespan is essential in managing longleaf and publicly held lands (National Forests, military reservations and National Wildlife Refuges) are about the only place where this type of long-term, patient management can happen.”

What is your advice?

Boyer – “The transfer of existing information into use is the hang up. We also have to get rid of the disincentives, from the greater cost of initially establishing longleaf to the various state and federal cost share programs that have funded only loblolly and slash pine planting and management by the private land owner. And we have to plan for the long haul.”

Farrar – “With a good burning program, longleaf will maintain itself. If you can’t do anything else – burn.”

Neel – “Use fire and use it frequently. Give the longleaf stand time. You have got to be patient.”

What is the Future of the Longleaf?

Although the exact acreage of natural longleaf pine forest remaining today is not known, it is clear that the ecosystem has suffered dramatic declines in area. Between 1955 and 1985, longleaf pine acreage dropped from 12.2 to 3.8 million acres – a decrease of 69% in just 30 years. Florida and Georgia saw a decrease of 75% during this 30-year period and every year more and more longleaf acreage is cleared for agriculture, suburban and urban development.

According to the U.S. Forest Service over 140,000 acres of longleaf are converted annually to other uses. Entire areas are clear-cut, site prepared, and converted to pine plantations. Almost all stands owned by industrial forest corporations have been converted to intensively managed short-rotation plantations. With the exception of a few hunting preserves, most privately owned stands have been cutover and left unmanaged.

Fire suppression has resulted in thousands of acres of prime longleaf land changing to dense scrub oak forests. Many of the few tracts that are dominated by longleaf pine are now being raked intensively for pine straw that is sold as a popular landscape mulch. Annual raking eventually eliminates the native ground cover and limits pine reproduction.

Overall, private owners account for 55% of the total longleaf acreage. In Florida, private landowners manage approximately 40% of the longleaf pine acreage, while in Georgia, they hold over 80%. The National Forests of the South contain about 700,000 acres of longleaf pine.

Although “multiple use” is the stated management plan, intense pressure to generate more immediate income from the forests is causing thousands of acres of native longleaf in our national forests to be converted to slash and loblolly pine monocultures. The longleaf pine acreage on Florida’s national forests, for example, has been reduced by one third since 1963. A similar decline has occurred on other publicly owned lands such as the military that controls over —– acres of longleaf.

Time is growing short to protect substantial and manageable acreages of this important ecosystem. Fortunately, today many public agencies are interested in perpetuating high quality longleaf forests that harbor endangered species as well as rehabilitating poorly stocked stands for production of timber and pine straw. For this valuable forest to continue emphasis must be placed on the perpetuation of multi- value forests by the private and public landowner and land manager alike.

How You Can Help Save the Longleaf

If you have a forest, burn it. Don’t convert it to trees growing in rows. Land management is the right of the landowner, so find a land management professional to help you manage it the way you want it managed. Once you understand the Longleaf dynamics then you can have a conversation with a forester to help you do this the way you want it done.

If you want to convert to Longleaf, you can have a productive forest eventually, and have pine needles in the mean time and something pretty to look at. You can plant it or simply rehabilitate what you have if you put fire back into your longleaf.

You can plant Longleaf if you have a site where it would grow well. Consider growing it anywhere in the South East, the historic range of longleaf. It won’t grow in a swamp interior, but it will grow almost anywhere else.

Another need is support for Longleaf research. Leon Neel describes the way he practices forestry as an art. He knows what he wants to do and he knows how he wants the forest to look and he manages it for that look. He packs in timber and when the landowner wants to make money, it’s there to cut. But there are no numbers for others to go by. If the data were available to know how much saw timber could be produced over how much time landowners would more readily convert to Longleaf Pine

Some Famous Quotes on Longleaf Pine

“Not a part of this great natural wonder worthy of the name forest remains intact within the state’s borders. It has been rooted out by hogs, mutilated by turpentining, cut down in lumbering, or burned up through negligence. The complete destruction of this forest constitutes one of the major social crimes of American history.” B.W. Wells, ecologist, 1932

“We find ourselves on the entrance of a vast plain which extends west sixty or seventy miles…. This plain is mostly a forest of the great long-leaved pine, the earth covered with grass, interspersed with an infinite variety of herbaceous plants, and embellished with extensive savannas, always green, sparkling with ponds of water….” William Bartram, 1791 Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia,...

“The irony is the Longleaf system used to be one of our most abundant ecosystems. The remaining Longleaf ecosystem is in fragments, and the fragments are under further threat. What once was an ordinary part of our environment, we have made rare.” Stephen Humphrey, Florida Museum of Natural History, 1993

“Taking fire out of the longleaf forest is like taking the rain out of the rain forest.” Larry Landers, Joseph Jones Ecological Center. 1992

Longleaf Pine, the most important text to date on longleaf, was written in 1946 by W. G. Wahlenberg. The inside cover declared Wahlenberg’s feelings, “Dedicated to a future in American forestry for one of the finest timber trees the world has ever known.”

“Longleaf is an efficient producer of high quality wood products even on deep sandy sites. It has supreme resistance to many of the hazards of the southern environment, e.g., fires, insects, disease, and has great aesthetic appeal.” Thomas C. Croker, Jr, Forestry Consultant. 1989

Early European travelers had mixed aesthetic views concerning the almost interminable pines, “wilderness more oppressive a thousand times to the senses and imagination than any extent of monotonous prairie, barren steppe, or boundless desert can be.” Fanny Kemble, English actress, 1838

Here’s to the land of the longleaf pine,

the summer land where the sun doth shine,

where the weak grow strong and

the strong grow great.

Here’s to “down home,”

The Old North State!

A Comparison of Three Southeastern Pines: Longleaf, Slash and Loblolly Longleaf Legacies

The young longleaf pine makes one of the most striking features of southern forests. When five to 10 years of age, the single upright stem with its long, dark, shiny needles, forms a handsome plume of sparking green; while in later youth the stalwart, sparingly branched sapling, with its heavy twigs and gray bark, attracts immediate attention. The old trees have tall, straight trunks, most one to two feet in diameter, and open, irregular crowns, one-third to one-half the length of the tree.

Longleaf stands, found throughout the southern coastal plain, today reflect a history of extensive naval stores operations, logging, and burning following the logging. As a result many longleaf pine forests have been replaced by other species.

The leaves or needles are from 10 to 15 inches long, in clusters of three, and gathered towards the ends of the thick, scaly twigs. The flowers, appearing in early spring before the new needles, are a deep rose-purple turning to silver-white The ample flowers grow in prominent, short, dense clusters, and the female flowers occur in inconspicuous groups of two to four.

The cones, or burrs, are six to 10 inches long, slightly curved, with thick scales armed with small curved prickles.

The cones usually fall soon after the seeds ripen, leaving their bases attached to the twigs.

The distinctive large cones develop from female flowers over a two year period. Seeds are dispersed by wind beginning in late October and continuing through November with most falling within a two to three week period depending on weather conditions.

Many animals, including wild hogs, fox and grey squirrels, and many types of birds feed on the large, tasty seeds. Longleaf seeds are the largest of the southern pines and differ from the others in that the seeds germinate soon after they reach the ground. If conditions are right they can germinate in less than a week.

Longleaf Pine

NEEDLES: 8 to 18 inches long, in clusters of 3, form dense spherical tufts at the ends of stout branchlets, slender, flexible

CONES: 6 to 10 inches long

SEEDS: with wing, 1 ½ to 2 inches long

FLOWERS: male: dark rose-purple; female: dark purple

Slash Pine

NEEDLES: 8 to 12 inches long, in clusters of 2 or 3, in tufts at the ends of branchlets, stout, rather stiff

CONES: 2 to 6 inches long

SEEDS: with wing, 1 ¼ inches long

FLOWERS: male: dark purple; female: pinkish

Loblolly Pine

NEEDLES: 6 to 9 inches long, in clusters of 3, slender but rather stiff, may be twisted

CONES: 3 to 6 inches long

SEEDS: with wing, about 1 inch long

FLOWERS: male: yellow; female: yellow

Forest Trees of Mississippi, Mattoon and Beal, 1929

Naval Stores & Turpentining

By Lawrence S. Earley

(Lawrence S. Earley is Associate Editor of Wildlife in North Carolina magazine. Larry has written many articles for that publication and other magazines, including Audubon, Nature Conservancy magazine, and National Parks. This text is taken from his notes for a book he is currently writing on the natural and cultural history of longleaf pine.)

Once Scottish liquor makers introduced the copper still in 1934, stills could be made just about anywhere in the piney woods. Turpentine and rosin production boomed. Barrels of spirits and rosin were transported, usually by water, to a port city. The main naval stores ports were, first, Wilmington, North Carolina, then Savannah, Georgia, and, finally by the early 1900s, Jacksonville, Florida.

Spirits of turpentine is a clear liquid separated by distillation from the raw resin (gum). After the distillation process is complete, the residue in the kettle, called rosin, is discharged and loaded into barrels. It hardens as it cools. Commercially valuable, it was sorted into t13 grades ranging from the lightest in color, and most valuable, to the darkest. Today, rosin is still used by many people, from ballerinas to baseball players.

As the vast longleaf forests of North and South Carolina played out, the turpentiners moved their equipment and men (box cutters, shippers, pullers and dippers) southward. They moved through Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi, ending up the early 1900s in Florida where naval stores production reached its peak in 1908. By the 1930s no virgin trees remained untapped.

Collecting the resin or gum was a labor-intensive effort involving teams of men with specific tasks. Some cut boxes in the bases of trees. Later as efficiency increased, clay pots or oblong tin trays (shown here) were attached to the trees. Angled cuts or streaks, ¾ inch wide and 1 inch deep, were made above the box or other container by chippers so that resin would flow downward into the receptacle. A “cat face” was created as the streaks were continued upward at the rate of about a foot a year. When the faces got so high that chippers couldn’t reach them, a puller extended the faces sometimes up to 20 feet above the ground. Every two or three weeks the resin would be collected in buckets by dippers and emptied into large barrels positioned throughout the woods. Mule-drawn wagons delivered the 50 gallon barrels to the still.

Tar burning may be a forgotten art, but is legacy is still with us in the nickname “Tar Heels,” a popular sobriquet for North Carolinians. Its origin is uncertain, but no doubt it reflects the importance of North Carolina in the early production of naval stores. Tar accumulated amidst the dirt and shoes around tar kilns and would stick to the workers’ feet—this is one way the name could have arisen.

Longleaf Pine-Dependent Industries

From “Longleaf Pine-Dependent Industries,” by Richard Porcher, The Citadel, Charleston, S.C., 1985.

Naval stores, tar and pitch supplies used by the Navy, were dwindling in the Northern European countries when the New World was discovered. But the production of naval stores and turpentine in this country did not actually begin in the South. The North Atlantic colonies began the process in the 1600s, where pitch pine was used. But as colonists began to arrive in North Carolina about 1665, they soon discovered that the abundant longleaf pine was a more prolific source of tar and turpentine. By 1700 the production of naval stores was an important part of the economy of North Carolina and quickly spread to South Carolina. In 1850 the Carolinas accounted for 95 percent of the total American production.

Crude turpentine is found in the resin canals of the inner bark and sapwood of various conifers. This gummy fluid is not the sap of the tree. Upon distillation, crude turpentine yields two components; essential oil (spirits of turpentine) and rosin. These products still have many uses today. Spirits of turpentine is important in the paint and varnish industry as a thinner. It is also used as a solvent for rubber, in medicine and in the manufacture of many chemicals. Rosin, a brittle faintly aromatic solid, is used in the manufacture of soap, varnish, paint, linoleum, sealing wax, drugs and oilcloth. It is the chief sizing material for paper.

But it was tar, not turpentine, that was most important in the early development of the South. Tar is the crude liquid that drips form the burned wood during slow combustion. Pitch is a partially carbonized and condensed product obtained by boiling or burning tar. Tar and pitch were among the earliest exports of the country, and the industry was about the only means of livelihood in the early days of the Carolinas. Indeed, the history of naval stores is closely identified with the economic development of the South. Pitch was used chiefly for caulking wooden sailing vessels and tar to coat the riggings. Eventually pitch was replaced by welding bead and the tarry rigging of sailing ships fell before the steam engine and diesel oil.

By the turn of the century, the vast longleaf forests of North and South Carolina soon played out, and turpentiners, a migratory lot, began to take their equipment and their help to Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida. By the 1920s, the last of the virgin longleaf forests had been cut throughout the Southeast. Second-growth timber was not as rich in gum as virgin timber, and chemical alternatives to naval stores began to be developed instead. The name “naval stores” continues to be used even though spirits of turpentine and rosin became the major products. Today, many other countries, including China and many South American countries, produce more turpentine and resin than the United States.

Grasses of the Longleaf Forest

By Julie Moore

Why did so many of the early southeastern visitors who traveled the piney woods refer to them as “savannas”? Because they felt they were moving through a sea of grass beneath a canopy of pines, sometimes densely packed, other times widely scattered. “Savanna” is a grassland with scattered trees, generally in tropical and subtropical regions.

Historian John F.H. Clairborne on a trip through woods observed, “Much of it is covered exclusively with longleaf pine; not broken, but rolling like waves in the middle of the great ocean. The grass grows three feet high and hill and valley are studded all over with flowers of every hue.”

The fuels that carried the lightening and man set fires come from two sources: the pine trees themselves providing needles and exfoliated bark and the ground cover, primarily the flammable blades of the grasses. Grasses provide fine fuels that dry quickly after rains and are easily ignited. Where pine trees are widely spaced, fire cannot spread without the fine fuel of grasses.

Mimicking the practices of native American inhabitants of the piney woods, stockmen burned the forests annually, mostly in late winter, to produce an abundance of succulent new growth in the spring for the unpenned (open range) herds of cattle, sheep and hogs.

Wiregrass (Aristida stricta and A. Beyrichiana), is the most characteristic and abundant grass the longleaf forest of carefully amidst the dense wiregrass other bunch grasses are found, such as the distinctive toothache grass with its curly one-sided heads that, if chewed, numbs the mouth and gums. Clumps of little bluestem, plumegrass, various panic grasses, broomsedge and piney woods dropseed may be found depending on soil fertility and available moisture.

Moving westward from Florida into Alabama and on into east Texas, wiregrass disappears and is replaced by an association of species commonly called bluestems (see map.) The grass diversity can be astounding with nearly a dozen short and tall bluestems, also called broomsedge or sagegrass, not to mention several threeawn grasses and panic grasses, switch grass, green silky scale, Indiangrass, gulf muhly and pine-barrens tridens. No wonder so many farmers of the Gulf Coastal plain fattened their cattle on the piney woods grasses in spring and summer after a winter spent in the swamps.

These grasses native to longleaf pine woodlands were important not only to herds of unpenned domestic animals; deer and even the woodland bison grazed their way through the piney woods. Gopher tortoises feed on the tender shoots after fires. And the seeds are important foods for quail, turkey and any number of song birds as well as rodents, the prey of hawks, owls and snakes. The dense cluster of leaves at the bases of these bunch grasses also provide cover for ground nesting birds as well as escape cover. Without the grasses, there can hardly be a longleaf forest.

Places to See Longleaf

- Zuni Pine Barrens. Isle of Wight Co., VA. An Old Dominion College and Virginia Nature Conservancy preserve. Northernmost remnant of longleaf pine/turkey oak forest, restoration in progress.

- Croatan National Forest. Carteret, Craven and Jones Cos., NC. Longleaf pine/wiregrass and longleaf pine/bluestem savannas, and longleaf pine flatwoods.

- Holly Shelter (State) Game Lands. Pender Co., NC. Longleaf pine/wiregrass savannas.

- Green Swamp Nature Conservancy Preserve. Brunswick Co., NC. Longleaf pine/wiregrass and longleaf pine/dropseed savannas.

- Bladen Lakes State Forest. Bladen Co., NC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak forest.

- Weymouth Woods State Natural Area. Moore Co., NC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak forest, with old growth longleaf stand on the Boyd Tract.

- Ft. Bragg Military Reservation. Hoke and Cumberland Cos., NC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak forest and longleaf pine savannas, sandhill seep.

- Sandhills (State) Game Lands. Richmond, Scotland and Moore Cos., NC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak, longleaf pine/mixed scrub oak forest.

- Camp Lejeune Marine Base. Onslow Co., NC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak forest, mesic and wet longleaf pine flatwoods and longleaf pine savannas.

- Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge. Chesterfield Co., SC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak forest.

- Sandhills Sate Forest and Cheraw State Park. Chesterfield Co., SC. Longleaf pine/turkey oak forest.

- Francis Marion National Forest. Berkeley and Charleston Cos., SC. Mesic and wet longleaf pine flatwoods, and longleaf pine savannas.

- Hitchcock Woods. Aiken Col, SC. Longleaf pine sandhill scrub and longleaf pine/scrub oak sandhill.

- Fort Stewart Army Base. Liberty and Bryan Cos., GA. Longleaf pine/scrub oak sandhill and mesic longleaf pine flatwoods.

- Okefenokee Swamp national Wildlife Refuge. Charlton and Ware Cos., GA. Longleaf pine savannas.

- Laura S. Walker State Park and Waycross State Forest. Brantley and Ware Cos., GA.

- Ft. Gordon Military Reservation. Richmond Co., GA. Longleaf pine/scrub oak sandhill.

- Ft. Benning Military Reservation. Chattahoochee and Muscogee Cos., GA. Longleaf pine/scrub oak sandhill.

- Red Hills Plantation Region. Grady and Thomas Cos., GA. Mesic longleaf uplands.

- Apalachicola National Forest. Liberty, Wakulla, Leon and Franklin Cos., FL. Longleaf pine savannas, longleaf pine mesic and wet flatwoods.

- Osceola National Forest. Baker and Columbia Cos., FL. Longleaf pine savannas.

- Ocala National Forest. Marion, Putnam and Volusia Cos., FL. Longleaf pine savannas.

- Blackwater River State Forest. Santa Rose and Okaloosa Cos., FL. Longleaf pine/scrub oak, sandhill and longleaf pine savannas, and sandhill seep.

- Eglin Air Force Base. Okaloosa, Walton and Santa Rosa Cos., FL. Longleaf pine savannas, longleaf pine mesic and wet pine flatwoods, longleaf pine/scrub oak sandhill.

- St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge. Jefferson and Wakulla Cos., FL. Longleaf pine savannas, longleaf pine mesic and wet flatwoods.

- Conecuh National Forest. Covington and Escambia Cos., AL.

- Escambia Experimental Forest. Escambia Co., AL.

- Talladega National Forest. Clay, Talladega, Cleburne and Calhoun Cos., AL.

- Reed Brake Research Natural Area. Ochmulgee District, Talladega National Forest. Bibb, Perry, Hale ad Chilton Cos., AL. Longleaf pine/scrub oak on clay hills.

- Bienville National Forest. Scott, Smith, Newton and Jasper Cos., MS. Longleaf pine woodlands.

- DeSoto National Forest. Perry, Forrest, Stone, Harrison, Jones, Wayne and Greene Cos., MS. Longleaf pine savannas.

- Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge. Jackson Co., MS. Longleaf pine savannas, sandhill seep.

- Homochitto National Forest. Franklin, Amite, Copiah and Wilkinson Cos., MS. Longleaf pine woodland.

- Kisatchie National Forest. Natchitoches, Winn, Grant, Rapides and Vernon Parrishes, LA. Longleaf pine/bluestem savanna and woodland.

- Alexander State Forest. Rapides Parrish, LA.

- Sabine National Forest. Sabine, San Augustine and Shelby Cos., TX. Longleaf pine/bluestem savanna and woodland.

- Angelina National Forest. Angelina, Nacogdoches, Jasper and San Augustine Cos., TX. Longleaf pine/bluestem savanna and woodland.

- Davy Crockett National Forest. Trinity Co., TX.

- Sam Houston National Forest. San Jacinto Co., TX.

- Big Thicket National Preserve, Hickory Creek Savanna Unit. Tyler Col, TX. Longleaf pine/bluestem.

- Roy E. Larsen Sandylands Sanctuary, a Texas Nature Conservancy Preserve. Hardin Co., TX. Longleaf pine/scrub oak sandhill.

Longleaf occurs on many other sites; State parks, The Nature Conservancy Preserves, land owned by camps, local conservation groups and more. For example, Florida is actively restoring longleaf on all of its state parks where longleaf once grew including the San Felasco Hammock State Preserve, Goldhead Branch State Park, Oleno State Park and Ichetucknee Springs State Park in the Northern Central Florida area alone. If you know good sits where the public can visit, let us know and we will add them to our next map.

The Longleaf Pine Poem

The Longleaf Pine Forests: Our Model for Living

By Yvonne Babb

The Longleaf Pine Forests:

our model for living,

our avenue for learning.

Have you sat beneath the longleaf watching,

for the sun to peer between the trunks so straight and tall?

Have you stopped to listen to the singing,

of the warbler, hawk or squirrel make its morning call?

Have you walked through wiregrass and flowers waving,

as the wind breathes life into them all?

Have you peaked into a gopher burrow,

felt sand that keeps it cool and moist?

Have you thanked the tree that gave us people,

wildlife, wood and rosin; yes it helped us,

survive the heat and troubles of the day?

Have you felt the joy of growing,

yes restoring, longleaf and its neighbors,

so the forest, Longleaf Forest will return?

To be special, something special,

to the people, yes the people,

of the southeast who have seen it disappear.

For the children, yes the children

of tomorrow, yes tomorrow,

who will then, have all the pieces of their past.

Yvonne Babb is an environmental education specialist who has developed a grade school program about the longleaf ecosystem. She has created a series of hands on programs, posters and a game called “Sandhill Survivors” where the children must help the forest animals get safely back to their burrows as a fire is approaching. Yvonne recently received a grant to continue evolving her curriculum throughout the Orange County School System. She lives with her husband, Geoff, and their twin sons in Babson Park, Florida.